This is second entry in our new series Archival Innovators, which aims to raise awareness of the individuals, institutions, and collaborations that are helping to boldly chart the future of the the archives profession and set new precedents for the role of the archivist in society.

Doug Boyd, Ph.D.

In this post, COPA member Vince Lee brings you an interview with Doug Boyd, Ph.D., Director of the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries. Dr. Boyd is a recognized leader regarding oral history, archives, and digital technologies. He recently managed the Oral History in the Digital Age, which was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Boyd currently leads the team that envisioned, designed, and is implementing the open-source Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS) system, which synchronizes text with audio and video online. He holds a PhD in folklore and ethnomusicology from Indiana University and previously served as the manger of the Digital Program for the University of Alabama Libraries, Director of the Kentucky Oral History Commission, and Senior Archivist for the oral history and folklife collections at the Kentucky Historical Society. He authors the blog Digital Omnium: Oral History, Archives and Digital Technologies, is the co-editor of the book Oral History and Digital Humanities published by Palgrave MacMillan in 2014, and Boyd is the author of the book Crawfish Bottom: Recovering a Lost Kentucky Community published in August 2011 by the University Press of Kentucky.

VL: Please describe your innovative project.

DB: In 2008 I designed a web application called OHMS (Oral History Metadata Synchronizer) to enhance access to online oral history by connecting a text search of a transcript or an index to the corresponding moment in the audio or video. OHMS is a 2-part system that includes the OHMS web application and the OHMS viewer. The web application is where you do the work of synchronizing a transcript or indexing your interview. When indexing an interview you create linkable segments that include a range of metadata fields that include the following fields: segment title, description, partial transcript, keywords, subjects, GPS coordinates, as well as hyperlinks which can be used to link the user to related web resources, or link the user to photographs.

The second part of OHMS is the OHMS Viewer. The viewer was designed to interact with a local CMS and can be incorporated in free systems such as Omeka or WordPress just as simply as it is integrated into more complex systems such as CONTENTdm, Islandora, or Blacklight. OHMS was designed to provide an affordable option for enhancing access to online oral history and it has transformed our workflow at the Nunn Center. Prior to launching OHMS, the Nunn Center was averaging 300-500 interviews that were being accessed each year. Today, Nunn Center interviews are being accessed online an average of 10,000-12,000 times per month. In 2011 the Nunn Center received a national leadership grant from IMLS to make OHMS open source and free. In 2014, OHMS was released to the public, and at this time, there are over 500 individual and institutional OHMS accounts in over 35 different countries.

VL: Where did you get your idea and what inspired you?

DB: Prior to working at the University of Kentucky I managed the digital program at the University of Alabama. During this time I thought a great deal about web usability and design, as well as the user experience working with digital library/archives platforms at the time, especially with regard to archived oral histories. Prior to my experience at the University of Alabama, I was the Senior Archivist for the oral history collection at the Kentucky Historical Society and had grown frustrated with the discovery and usability challenges posed by archived oral history (and all time based media). Most oral history interviews are not transcribed, which creates a great deal of challenges for both the archivist and the user. The result was that the rich interviews in our oral history collections were mostly going undiscovered and ignored. I began thinking about possibilities. The digital program at the University of Kentucky had experimented with time-coded access to online oral history, but this required manual markup of a transcript. OHMS grew out of my obsession with enhancing access to archived oral histories, but also to create empowering opportunities for more sustainable workflows in the archive.

VL: What worked? What didn’t work? Were you surprised by the outcome or any part of your experience?

DB: Developing OHMS was definitely an iterative process. Keep in mind, we originally designed OHMS to work only with the Kentucky Digital Library, our primary access point at that time. Also, initially OHMS only worked for synchronizing transcripts. One of my favorite innovations of OHMS was when we designed the indexing feature. Indexing really has been transformative for us, and now for so many individuals and institutions. It provides an option for enhancing access to untextualized oral histories when transcription was not a financial or practical reality. Last year the Nunn Center put over 900 indexed interviews online. If we had transcribed all of those interviews, it would have cost the center over $250,000, which of course we would not be able to afford. We would have only been able to provide online access to about 75-100 interviews that year. One of the overarching goals for OHMS from the beginning was to create more sustainable workflows that were both effective and efficient, and that has clearly worked very well.

What did not work? The original plan was to have the OHMS Viewer be a plugin for 3-4 popular content management systems. Once we really sat down at the table to talk about this it became abundantly clear that we would never be able to maintain and grow that approach after the grant ran out. While this meant that the OHMS viewer was not as integrated as it could have been with a select few content management systems, it meant that there were fewer dependencies, making the OHMS Viewer portable enough to interact easily with any system.

VL: What would you do differently?

DB: Automating account setup far earlier in the development journey. It was not until this last development cycle that we automated the account setup process. Manual setup of each account was fine in the very beginning when there were few OHMS accounts beyond our internal use at UK. It was such an honor to interact with so many wonderful oral history projects around the world. However, there came a point where I was manually setting up 10-20 accounts each week. Automating account setup had been on the development roadmap for several years, however, it kept falling down as a priority. I would always ask questions such as “do we make OHMS bilingual, or do we make things easier on me.” The last year or so automation became essential as so many account requests were coming in. While this does make things easier on me, it really is an important step toward sustainability.

VL: What tips do you have for budding innovators?

DB: It sounds cliché but do not be afraid to experiment. The original version of OHMS was created and launched for $10,000 using internal funds (not a grant). While $10,000 is an incredibly large amount of money, for a digital project, this is extremely affordable. We found an creative programmer, drew up many designs on napkins and moved forward with development. Also, think about sustaining your innovation early in the process. While we did receive an IMLS National Leadership Grant, we had already created and implemented OHMS several years prior to getting the grant. All of our development since the 2011 grant has been internally funded. You can do magical things with a grant, what you cannot always do is sustain the work once the grant has run out. I am pretty proud that we have designed OHMS to be sustainable whether there is a grant in play or not.

VL: Did you get media attention? How did that happen?

DB: We have received wonderful attention. In a way, this attention was not driven by OHMS, but by the enhanced discoverability of the oral history material being delivered via the OHMS Viewer. Often the media is first drawn to the contents of the interviews, and then they have the “a-ha” moment where they realize how amazing the interface is. Additionally, I have lectured a great deal about OHMS, which has raised general awareness of the tool within the oral history and archives community. I have spoken about OHMS throughout the United States, in Australia, China, the UK, and several countries in Europe. When I go on the radio, or when I narrate our podcast The Wisdom Project, I will give OHMS a brief mention. I will say something to the effect “You can listen to these interviews in their entirety using our magical search system called “OHMS,” a system we developed at the Nunn Center.” While this sounds self-promotional, it is intending to raise general awareness and plant seeds. While media attention is important, it is vitally important to raise general awareness of OHMS among the audience that OHMS is serving, so I get as excited about a mention on a student blog, or in The Signal (a blog published by the Library of Congress) than I do about articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education or a mention on NPR.

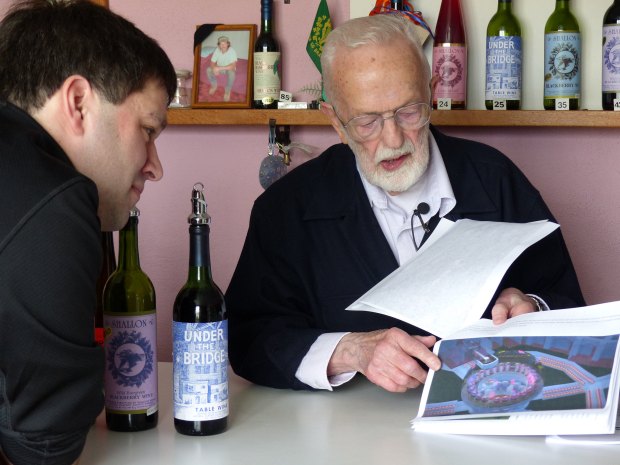

Boyd working with a colleague on an oral history interview in OHMS.

VL: Do you have a collaborator? If so, how did you find them?

DB: Definitely. Internally, our team at the Nunn Center and University of Kentucky Libraries have been critically important. Eric Weig, Mary Molinaro, Kopana Terry, Danielle Gabbard, and Michael Slone have all played essential roles in making OHMS a practical reality. When you are at an academic institution working on a project like OHMS development, the Deans of University of Kentucky Libraries (Terry Birdwhistell and Deirdre Scaggs) continue to be essential collaborators. Jack Schmidt was the original programmer who we contracted to write the original code. Externally, each programmer who has worked on OHMS has been an essential collaborator, especially Shawn De Cesari who worked for the company we contracted to rewrite the code during the IMLS grant. Recently, we have worked closely with AVPreserve on the development of OHMS and this collaboration has proven incredible with regard to helping me shape the vision and development direction of OHMS. In each case, programmers who have worked on OHMS have been so much more than just work-for-hire programmers, each one bought in to the mission and vision of OHMS and have always delivered far more creatively than they were being paid for.

The other collaborators who are critical to mention are those early adopters of OHMS who continue to give amazing feedback about development and usability priorities. Institutions like the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia and the Brooklyn Historical Society were critical early on in the process. These institutions took a chance on OHMS early on and gave profoundly important feedback early on. More recently, working with organizations like Oral History in the Liberal Arts, the students and faculty at West Chester University, as well as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences have been important on the development of OHMS as a pedagogical tool (more on that later) as well as shaping my work in adding the bilingual aspects of OHMS.

Finding collaborators is about recognizing the opportunities and proactively empowering those collaborators to feel part of the process, part of the team. Now, our collaborators are broadening out to other institutions, such as Indiana University, who have begun to collaborate on the development of OHMS and help take the system to the next level. Indiana University recently contracted AVPreserve to add Avalon capability to OHMS, which has been transformational on many levels. I am very excited about seeing what comes next with regard to collaborators on development.

VL: Did you have institutional, administrative, or financial support for your project? How did you go about securing that support?

DB: As mentioned above, I initially funded development using some Nunn Center endowment funds that had accumulated over a few years prior to me coming to the University of Kentucky. The Deans and Associate Deans at the University of Kentucky have always been open to experimentation and they all gave me the space to move something like OHMS from the idea phase into actuality. Having their trust was essential to securing the initial internal funding. Externally, we did receive an IMLS National Leadership Grant in 2011. This was a critical development as it provided the support needed to rewrite the entire code and rethink OHMS as a system that people outside of the University of Kentucky could use.

VL: What’s next? Either for this project or a new development?

DB: I have received a Fulbright Research Grant to spend 6 months in Australia to work with the National Library of Australia. The NLA created a system similar to OHMS. The Fulbright grant is a way for us to collaborate in a substantive way on how we can work together to elevate both systems and explore international standards for enhancing access to online oral history. We are moving in to the next active development stage where some exciting things are happening. Most importantly, when I return from Australia, the top priority is to establish an institutional consortium that will help guide and sustain OHMS development moving forward.

VL: What barriers or challenges did you face?

DB: Of course, the major barriers are always funding and available resources. Again, I am proud that we have been able to sustain the work of OHMS long after the IMLS grant was complete, but major paradigm-shifting development will need more grants. Upon completion of the grant there were some aspects of OHMS hosting and minor development that fell to programmers at the University of Kentucky Libraries. We have very talented IT staff, but OHMS hosting and development had to be absorbed and balanced with many competing (and sometimes conflicting) priorities. We have since moved hosting and development to AVPreserve, which has been an incredible experience. We have expedited development and OHMS is no longer a conflicting/competing priority for the UK Libraries IT staff. This really was a great move on so many levels.

Of course, OHMS is no longer something that only serves the Nunn Center. Since there are OHMS accounts in over 35 different countries, I need to think about OHMS accounts and users on an international scale when making even small development decisions. Last year some of our international partners reported that the OHMS Viewer was not effectively searching characters utilizing diacritics. As a result, we had to shift some priorities around. While this is neither a barrier nor a challenge, it is an exciting shift in focus for me to have to think so broadly about our development roadmap.

VL: Were you able to leverage help from students, interns, or grad students for technological or experiential aspects of the project?

DB: Absolutely. We have a full team of student indexers at the Nunn Center who have provided incredibly valuable feedback on OHMS development, as well as on the resources and tutorials that we have created on using OHMS.

VL: Are there plans for implementing this project in curricula or as a resource to faculty/students?

DB: Absolutely. First, the Nunn Center’s collections are now accessed on a massive scale. As designed, OHMS has enhanced discovery and usability, and as a result, faculty and students are using oral histories in the classroom on a much larger scale. However, there has been an unexpected shift in how OHMS is being used in the classroom. Even before OHMS had been released publicly to other institutions, I started using the back-end of OHMS in the classroom. Specifically, students were assigned indexing projects in my graduate and undergraduate classes. After the first semester, I very quickly realized that OHMS could be utilized as a powerful pedagogical tool. Since then, we have collaborated with several professors at the University of Kentucky, as well as at Universities around the country who are designing entire courses around using OHMS to work with oral history in the classroom in powerful and effective ways. The Going North and Philly Immigration projects at West Chester University, the Jewish Kentucky project here at the University of Kentucky are some higher profile examples, but smaller scale classroom initiatives are popping up around the country allowing the archives to engage faculty and students in new ways. Additionally there have been several recent journal articles in the Oral History Review focusing on OHMS as a pedagogical tool, as well as the article “Connecting the Classroom and the Archive: Oral History, Pedagogy, and Goin’ North” featured in Oral History in the Digital Age.

VL: How did you use this project as a catalyst for getting different groups to talk to each other (cross-generational, cross-cultural, etc.)?

DB: OHMS has transformed access to our oral history collection at the Nunn Center. In 2008 we had 300-500 interviews being accessed annually. Now the number averages 10,000-12,000 each month. This level of access has perpetuated a renewed interest in oral history at my institution. The Nunn Center is currently maintaining over 50 interviewing initiatives at any given moment, which has connected us to new communities around Kentucky, as well as working with communities and individuals on a national and an international scale. We used to work only with projects on the state-level, however, now we have projects all over the United States, as well as in Haiti, India, Pakistan, as well as a current interviewing project in Ecuador. This volume of oral history is, by definition, catalyzing connection. Much of this success is due to the success of OHMS and our commitment to enhancing access to our archived oral history interviews.

VL: What was your institution like before you joined? Does your institution have a history of supporting innovation in archives?

DB: The Special Collections Research Center in the University of Kentucky Libraries has had a history of experimentation and early adoption. One of the things that drew me to the University of Kentucky in 2008 was the fact that I knew I could work very closely with the digital program. So I came in to a context that was supportive and curious.

VL: What was your strategy for shifting the culture of your institution to be open to your innovative projects?

DB: Honestly, I did not have to do much beyond earning the trust and confidence of leadership. I was able to recognize a problem—major discovery and usability challenges to accessing oral history—and articulate a potential solution. I am a big believer in creating a “proof of concept” which is what we had when we built the initial version of OHMS. Once leadership saw OHMS in action, there was very little convincing that was needed at that point.

Chris Burns: Where did you get your idea and what inspired you?

Chris Burns: Where did you get your idea and what inspired you?