This post was authored by guest contributor Gene Hyde, Head of Special Collections at University of North Carolina Asheville

Undergraduate research is a hallmark of the University of North Carolina Asheville, the state’s designated Public Liberal Arts University. As part of this institutional mission, we in Special Collections work closely with the History Department and other departments to incorporate primary materials into the research process. This is the tale of how Special Collections worked with one particular class, History 373.

History 373, taught by Dr. Ellen Pearson, was the first digital humanities course at UNCA. The class was small, with three teams of students, each working with a collection or collections. Their assignment was to conduct research using primary materials from Special Collections as well as other primary and secondary materials, then write and create digital humanities projects rather than traditional papers. We planned one class session for the student teams to select the collections they would be using for their projects, and we selected a “speed dating” process to introduce them to the collections.

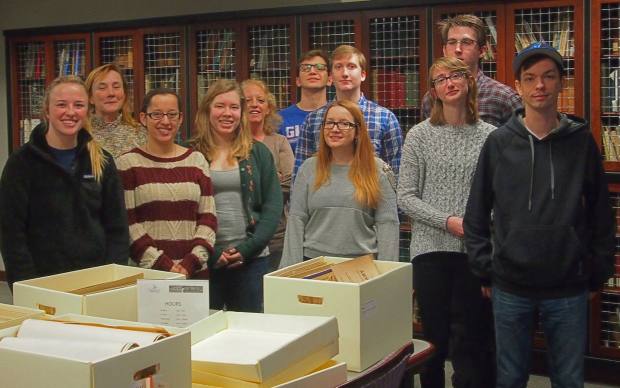

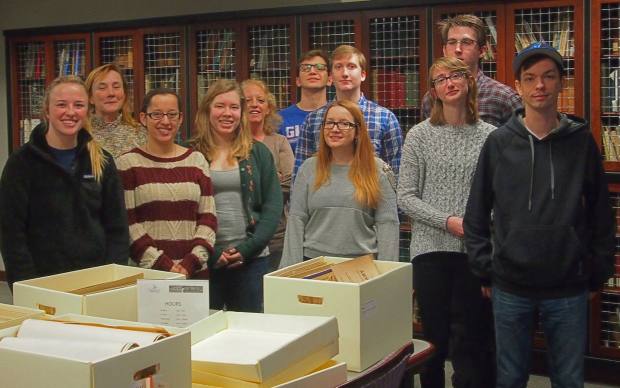

Digital History class at UNCA with Professor Ellen Pearson

The role of Special Collections in this process was somewhat traditional in that we were serving as a resource for materials rather than supporting the technological issues and platforms that digital humanities projects entail. For the technology side, the class was also paired with a Computer Science class and had extensive support from the library’s Media Design Lab.

Knowing that this was a one-semester project, we kept certain parameters in mind as we curated collections for this “speed dating” class, selecting collections that met the following criteria:

- We came up a with an initial list of a dozen or so collections, then consulted with Dr. Pearson. She took the topical pulse of the class, and we narrowed it down to six collections covering three basic themes in local history. The students had access to the finding aids for these six collections prior to the class.

- To facilitate the visual component of digital humanities, we selected collections that had maps, photographs, brochures, newspaper articles, and other images in addition to manuscripts.

- The collections each had a “full tale” to tell – that is, there was enough documentation in one or more of these collections to craft a complete narrative within the span of one semester.

- We kept copyright in mind, opting for collections where we owned the copyright, the collections contained public documents, or we knew that copyright could easily be secured. We knew that some students would probably want to use entire articles from the local newspaper in their digital projects, so I made a quick call to the managing editor and secured permission for this. Special Collections regularly provides them with photos for local history columns and they were glad to reciprocate for student projects.

- We located other collections that complimented the collections we were suggesting. For instance, we owned the city record documenting a downtown mall development proposal, and special collections at the local public library had the records of the citizens groups that fought the downtown mall development project. We work closely with the archivists at the public library, so I called and gave them a heads up about what we had in mind for this student project. They were delighted to help the students, and access to both the city and the citizens’ group records were critical in the success of that project.

Why this emphasis on pre-selecting collections? UNCA requires a final capstone research project for all majors, and we have seen some students struggle to settle on a research topic. We also knew that, in addition to choosing a topic, some might experience learning curves with the technology involved in Digital History projects. For these reasons, Dr. Pearson and I agreed that pre-selecting particular collections for the students to choose from would allow the students to concentrate on their research and mastering the technology.

When the class came in, we had arranged representative materials from the six collections on tables around the reading room – setting the stage for “speed dating.”

We walked around and introduced each collection to the students, describing the content, research possibilities, and the kinds of images and graphics in each collection. We also noted when there were related collections (at UNCA and the public library) that would help with their research.

We laid down basic ground rules for handling collections – only remove one folder at a time, respect the original order within the folders, and only use pencils, laptops, or cell phone cameras. Each team could spend five minutes to “date” a collection, then it was time to move on. We then cut them loose on the collections!

The three teams quickly fanned out and began examining the collections, moving to different ones, talking with each other, asking us questions, and conferring with Dr. Pearson. We circulated and provided more context about the collections, pointing out useful related materials that were not on display in the reading room that they might find helpful.

The reading room was abuzz with activity and collaboration, and it was clear that a number of students were excited about what they were finding. As they settled in and began looking deeper into the collections, talking waned and serious examination began to take place.

The reading room was abuzz with activity and collaboration, and it was clear that a number of students were excited about what they were finding. As they settled in and began looking deeper into the collections, talking waned and serious examination began to take place.

Dr. Pearson then told everyone that “the first team to claim a collection gets it,” resulting in some friendly competition between the teams as they jostled to claim their favorite collections. Selections made, the teams were then ready to start their research.

Over the course of the semester the three student teams were regulars in the Reading Room. We assisted them with documents, helped them with scanning, consulted on finding secondary materials, helped them navigate copyright issues, and generally helped them with the primary resource component of their digital history projects.

Feedback from the students and Dr. Pearson was very positive – they found the “Speed Dating” to be an effective way to gain a short, intensive immersion into each collection’s possibilities.

Feedback from the students and Dr. Pearson was very positive – they found the “Speed Dating” to be an effective way to gain a short, intensive immersion into each collection’s possibilities.

A news article about the project with a photo of the Downtown Mall Project group (taken in Special Collections) was posted to the UNCA webpage, which highlighted the role of Special Collections in the process.

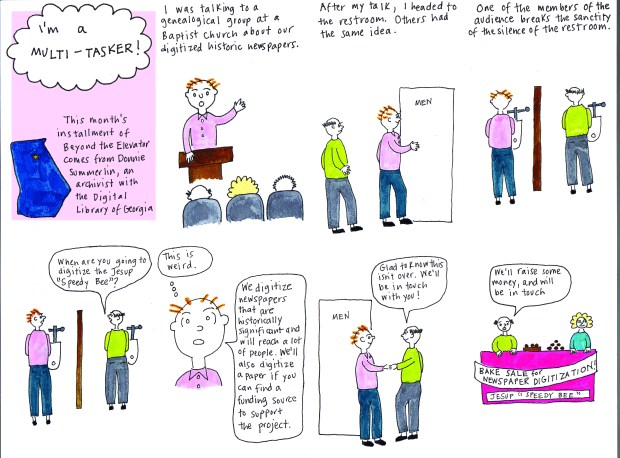

Beyond the Elevator is a cartoon strip created by Mandy Mastrovita and Jill Severn. The strip expresses their heartfelt belief that the magic of archives can and should be worked into ANY conversation or situation. The prospect of this axiom has exhorted the two into paroxysms of giggles, chortles, and howls despite the sober and noble subject matter. Indeed, they have spent hours cooking up likely scenarios to bring to life in future cartoons. These little gems appear in ArchivesAWARE! on amonthly basis for the foreseeable future, or until they run out of ideas. Which is where you, the reader can help. Tell them your best stories about talking archives—the wilder, the weirder, the crazier; the better. They will even take an elevator story if you make it good. To share your story, please send a description of your concept, relevant details, and contact information (your name and your email address) to beyondtheelevator@gmail.com.

Beyond the Elevator is a cartoon strip created by Mandy Mastrovita and Jill Severn. The strip expresses their heartfelt belief that the magic of archives can and should be worked into ANY conversation or situation. The prospect of this axiom has exhorted the two into paroxysms of giggles, chortles, and howls despite the sober and noble subject matter. Indeed, they have spent hours cooking up likely scenarios to bring to life in future cartoons. These little gems appear in ArchivesAWARE! on amonthly basis for the foreseeable future, or until they run out of ideas. Which is where you, the reader can help. Tell them your best stories about talking archives—the wilder, the weirder, the crazier; the better. They will even take an elevator story if you make it good. To share your story, please send a description of your concept, relevant details, and contact information (your name and your email address) to beyondtheelevator@gmail.com.

The reading room was abuzz with activity and collaboration, and it was clear that a number of students were excited about what they were finding. As they settled in and began looking deeper into the collections, talking waned and serious examination began to take place.

The reading room was abuzz with activity and collaboration, and it was clear that a number of students were excited about what they were finding. As they settled in and began looking deeper into the collections, talking waned and serious examination began to take place. Feedback from the students and Dr. Pearson was very positive – they found the “Speed Dating” to be an effective way to gain a short, intensive immersion into each collection’s possibilities.

Feedback from the students and Dr. Pearson was very positive – they found the “Speed Dating” to be an effective way to gain a short, intensive immersion into each collection’s possibilities.