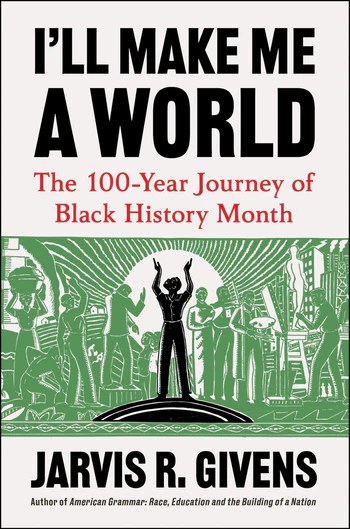

In his new book, I’ll Make Me a World : The 100-Year Journey of Black History Month, award-winning author and acclaimed Harvard scholar Jarvis R. Givens unpacks the events that led from the establishment of Negro History Week in February 1926 to the declaration of a month-long celebration in February 1976. His discourse draws on black historical knowledge shared by black memory workers in traditional, cultural, and personal ways that contribute to the counter-narrative of black history that is often under attack today. With permission from the publishers, COPA member Sidney Louie shares excerpts from Dr. Givens’ introduction to I’ll Make Me a World.

The year 2026 marks the one hundredth anniversary of Negro History Week, which was established in February 1926 by famed educator and historian Carter G. Woodson, then expanded to Black History Month in 1976. This milestone presents an opportunity to reflect on the black historical tradition, a critically important task given the current political conflicts pertaining to what can and cannot be taught about race and history in American schools and colleges or engaged in public spaces. Such critical reflection is the purpose of I’ll Make Me a World, which commemorates the one-hundred-year journey of Black History Month by deeply engaging the tradition that informed its creation.

To thoughtfully engage this legacy, I will employ the language of “black memory work” and “black memory workers” as capacious terms borrowed from black women archivists to describe the enterprise of recovering, preserving, and bearing witness to black history. I do so because any sincere appreciation of this tradition demands recognizing a diverse cast of characters. It requires recognizing professionals engaging in historical work as their primary occupation, such as academics, archivists, museum curators, and schoolteachers, while also acknowledging a collective of black memory workers that includes the likes of community storytellers, youth activists, preachers, filmmakers, political organizers, poets, and musicians, as well as family members who preserve old photographs marked by handwritten descriptions that can be passed down to a nephew generations later. Black memory work has been sustained by many hands. It can also be traced to many places: formal archives as well as less formal collections containing ephemera paperclipped together in old suitcases. This tradition is concerned less with rigid boundaries drawn around the broader historical enterprise and more with where we can look to find the most truthful and expansive visions of black life, especially histories of everyday black people, their social worlds, and their beliefs.

Black History Month is a national observance in the United States that extends from this longer and more expansive tradition of black memory work. Over the span of the last hundred years, this tradition has seen many twists and turns: many wars in the international arena, many social movements and technological developments, many shifts in the political-economic character of the nation and global marketplace, and indeed many shifts in the racial regime that colored such social developments. Across these historical transformations, black people have experienced many gains and also many backward steps. Freedoms have been won, and they have also been taken away. All the while, knowledge about the past has been one of the most important resources for sustaining black life despite the external realities of antiblackness. For indeed, authentic accounts of the black past have described the tension between such realities without compromising their honesty about one or the other. They remind us, as African American studies scholar Imani Perry has written, that “Joy is not found in the absence of pain and suffering. It exists through it.” Historical accounts by African American memory workers like Perry have clarified that while “racism is terrible, blackness is not.”

Yet the “black” in Black History Month is often stripped of its political significance. The same can be said of contemporary teaching about the black past in schools and public memory, which is often done in extremely sanitized and reductionist fashion. By this I mean that public engagement with the heritage of African-descended people has drifted far away from resembling authentic black history, leading many black memory workers to say that the tradition has lost its criticality. These are legitimate concerns, and they are not new. African American historians raised similar concerns in the 1970s, just as the weeklong observance of black history as being expanded to a month. Their deliberations leading up to 1976, as what was originally Negro History Week became Black History Month, are revelatory for present-day assessments of the state of our national observance of black heritage.

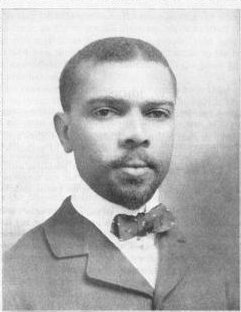

This book’s title, I’ll Make Me a World, is taken from the first stanza of “The Creation,” a 1927 poem by the educator, writer, and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, the author of “Left Every Voice and Sing,” which he wrote in 1900, after which it gradually became known as the black national anthem. Johnson’s song and poem were sung in segregated schools and recited by black youths, not only during the commemorative celebrations in February but as recurring rituals in the everyday. I draw inspiration from his poem about God creating the world in six days, because its themes of agency, imagination, and building reflect important elements in the story of Black History Month’s origins; these themes are reflected in the content of historical narratives from the black past, and they are also expressed through the actions of the African Americans who created and sustained the tradition of black memory work: the narrators, the archivists, the artists, and the memorializers. Indeed, the struggle to construct more expansive and honest narratives about the black past has always been an essential part of black people’s work to envision and shape a new world not predicated on their suffering.

Jarvis R. Givens is a Professor of Education and African and African American Studies at Harvard University. He is also the co-founding faculty director of the Black Teacher Archive. Published by HarperCollins, I’ll Make Me a World is now available in bookstores.

I’m at the airport waiting to board a plane when a fellow traveler strikes up a conversation. After we’ve commiserated about the shortcomings of the airlines and swapped details on destinations and reason for travel, I know what question is coming next: “So what do you do?” If you’re a new professional like me, you may remember your earlier responses to this question. Mine probably ended up somewhere between a frenetic rattling off of responsibilities and an apology. As the boarding began, I knew that my co-passenger had no idea what I did and was probably pretty certain I didn’t either.

I’m at the airport waiting to board a plane when a fellow traveler strikes up a conversation. After we’ve commiserated about the shortcomings of the airlines and swapped details on destinations and reason for travel, I know what question is coming next: “So what do you do?” If you’re a new professional like me, you may remember your earlier responses to this question. Mine probably ended up somewhere between a frenetic rattling off of responsibilities and an apology. As the boarding began, I knew that my co-passenger had no idea what I did and was probably pretty certain I didn’t either.