This is the latest post in our There’s an Archivist for That! series, which features examples of archivists working in places you might not expect. COPA member Anna Trammell, University Archivist and Special Collections Librarian at Pacific Lutheran University, brings you an interview with Rich Schmidt, Director of Archives and Resource Sharing at the Nicholson Library/Oregon Wine History Archive at Linfield College.

Rich Schmidt, Linfield College director of archives and resource sharing, poses with a photograph of Frances Ross Linfield. Mrs. Linfield’s donation in 1922 helped secure the school’s future and gave McMinnville College its new name.

AT: How did you get your job?

RS: I was hired at Linfield in the summer of 2011 as the Director of Resource Sharing, essentially running Interlibrary Loan. I have a background in digitization – and had worked closely with the archives in a previous position – but never had officially worked in the archives. Just after I started, Linfield hired Rachael Woody as the school’s first-ever full-time archivist and officially launched the Oregon Wine History Archive (OWHA). After about a year, she and I both had our legs under us – we’d hired and trained students in our departments and implemented new software and workflows. Rachael needed help growing the archives from that point, and I had time available to help.

The timing just worked out well. I had no background in wine, either, so the first couple years were like climbing a waterfall. So much information, so many people and dates and terms. But I loved it. Rachael was a great teacher and she and I worked really well together. We spent the next few years figuring out what exactly we wanted the archives to be, adding collections and making connections in the community. When Rachael moved on in 2017, the school entrusted me to keep the archives going, and so far so good. It’s busy, exhausting, fun and pretty exhilarating. I should mention that in addition to the OWHA, I’m also in charge of Linfield’s school archives, as well. So a lot of materials from wildly disparate places.

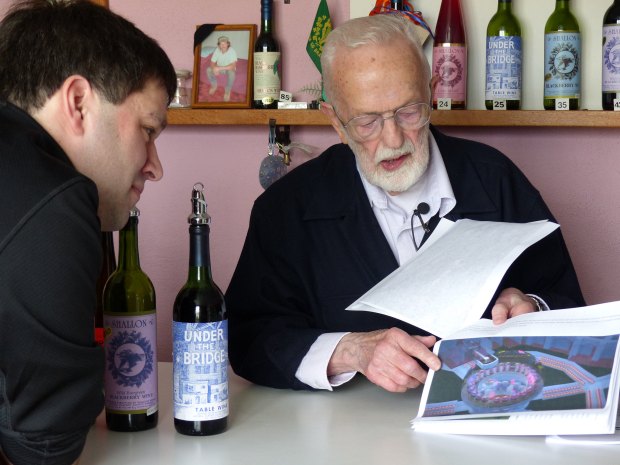

Rich Schmidt (left) interviews Paul van der Veldt at Shallon Winery in Astoria, Oregon, on March 30, 2017.

AT: Tell us about your organization.

RS: The Oregon Wine History Archive is dedicated to preserving and sharing the Oregon wine story. Wine in Oregon goes all the back to the Oregon Trail days, as there are stories of pioneers bringing vines across the country. There were farmers making table wine through all those years, often just enough for themselves and their neighbors, occasionally enough to sell a little. Never anything that you would consider an industry.

Prohibition – Oregon’s was the second-longest in the country, behind only Utah – wiped out most of the state’s winemaking, and the 30 years after Prohibition saw a few wineries spring to life across the state, mostly making table wine or fruit wine. In the mid-1960s, a group of young winemakers saw potential similarities between Oregon’s Willamette Valley and Burgundy, and set out to see if they could grow cool-climate grapes akin to the famous French region. From this handful of farmers, the industry very slowly grew. The well-known Burgundian varietals Pinot noir and chardonnay were the grapes of choice. Small snippets of international recognition came in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the industry still numbered fewer than 50 wineries and none of them were wildly successful.

A number of factors – including technological and educational advances, joint marketing efforts, success at national and international competitions, dogged determination, and just making really good wine – led to the industry finding solid footing in the 1990s, and then exploding in the 2000s. Thirty years ago there were around 50 wineries in the state; 15 years ago there were about 250. Now there are nearly 800, and more are coming seemingly every week.

We were founded in the midst of that, so we’re documenting an industry that is seeing amazing growth and establishing itself on the international market. Oregon has become known for Pinot noir, enough so that the International Pinot Noir Celebration is held every July right here on Linfield’s campus. Many of the industry’s founders are still around and living in the area, so we’ve been able work directly with them and their collections. This is such a huge benefit for our students, who are all undergraduates doing graduate-type work with our collections.

Linfield students Maia Patten (’16), Anna Vanderschaegen (’18) and Camille Weber (’16) join Rich Schmidt and Rachael Woody on a tour of Chateau Bianca Winery in Dallas, Oregon on July 20, 2015. Winemaker Andreas Wetzel (far left) gives the tour.

AT: Describe your collections.

RS: We were founded with the idea of being a traditional archive – that is, a brick and mortar space to collect materials. So that’s part of what we do. We house approximately 35 collections containing photographs, tasting notes, harvest records, grape sales documentation, awards, correspondence, journals and everything else you might expect to find. Wine is especially interesting because, while the end product is glamorous, all the processes that go into it are not. In most ways it’s just like farming any other crop, except you have to wait for your crop to turn into wine. So we have records that focus on the farming, records that focus on the winemaking, records that focus on the sales and marketing. Not to mention wine labels and statistical surveys and angry letters from consumers.

We also have a good collection of wine books and journals, some pertinent to Oregon and some with an international focus. For a young archive about a fairly young industry, we have a nice, diverse group of collections that show a nice cross-section of Oregon wine history. Due to the fact that the industry is still young and growing rapidly, and the fact that many wineries are family businesses passed from generation to generation, we realized early on that we couldn’t count on regularly receiving physical collections from the industry. If we were going to make an bigger impact, we’d have to archive in a different way, which led us to oral history interviews.

Rich Schmidt (right) interviews Remy Drabkin at Remy Wines in McMinnville, Oregon, on May 9. 2017.

There are so many people involved in the industry – some for 50 years, some for two years, some in farming, winemaking, sales, marketing, consulting, not to mention sommeliers and restaurateurs – that we realized we could let people tell their stories and really have an impact. This allowed us to make connections and gather stories from throughout the state and throughout the industry. The grape-growing geography of Oregon is spread from Portland all the way down to Ashland, and all the way over to Baker City. A huge amount of land spread out over a large state. Gathering oral history interviews from as many people as we can, in as many locations and roles as we can, has allowed us to maximize our resources and tell the biggest story we can.

We’ve conducted or gathered more than 250 oral history interviews already, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. But it’s been an amazing way to learn about the industry, its people, places, history, stories, past, and future. Our students research our interviewees’ backgrounds and come up with questions, then handle the cameras, microphones and post-production. Some even conduct all or part of the interviews. It’s an amazing experience for them.

From left: Rich Schmidt, Rachael Woody, Andrew Beckham and Annedria Beckham. Andrew and Annedria Beckham own Beckham Estate Vineyard in Sherwood, Oregon. Rich Schmidt and Rachael Woody interviewed them about their Oregon wine story on March 24, 2015.

AT: What are some challenges unique to your collections?

RS: We like to say that our archive is full of stories, not facts. Industry data from before the past 20 years is difficult to find, so questions about who was the first/biggest/best/most expensive almost always need to be hedged. Again, we’re looking at an industry that’s roughly 55 years old, so you’d think we’d be in better shape! But the early winemakers and grape-growers were concerned about a lot of things, very few of which dealt with keeping detailed statistics about every move they made. And much of the early numbers that were kept, of course, didn’t survive to make it into our archive. So we have a lot of stories, a lot of guesses, a lot of assumptions, and not a lot of hard truths. And honestly, that’s usually ok. Why let facts get in the way of a good story?

As the industry has grown, though, there’s a lot of interest in what the early grapegrowers tried, and whether it might work again with modern technology and practices. A side effect of the rapid growth of the industry is that competition has never been tighter. There are 500+ wineries in the Willamette Valley, mostly making really good Pinot noir. Many make between 5,000 and 20,000 cases of wine per year. What differentiates you from your neighbor, then? Many young winemakers are looking to the past to see if there’s a different clone, different varietal, different method that might make them stand out, and so there’s more of a push for facts now. We’re working with the early grapegrowers on gathering the data we can and making it available for the next generation of the industry.

For our physical collections, our challenges usually have to do with condition of materials. Many have been housed in barns, trailers and other unsuitable places, so we deal with vermin, bugs, water damage and all the other glamourous problems that archivists talk about over drinks. My students get a crash course in archival cleaning and processing less-than-pristine materials. At least they have great stories to tell their families and friends. Right now, it’s only me and five undergraduate students working in our archive, so each of them have to take on a much bigger role than you might expect. They are truly amazing. The archive couldn’t function without dedicated students, some of whom have an interest in archives work and some who have an interest in working in the wine industry. Work in the OWHA for a few years and you will meet a huge number of people in the industry and see many of the sites and potential jobs. How cool is that?

Linfield student Mitra Haeri (’14) uses a laptop and a portable scanner to digitize images in the back of a van at the Doerner family home in Douglas County, Oregon. The Oregon Wine Board funded this trip through a grant, allowing Linfield to spend a week in the Rogue Valley and a week in the Umpqua Valley, the two main grape-growing areas in southern Oregon.

AT: What is your favorite part of your job?

RS: I’m lucky because I really like what I do. I love working with students who are so eager to learn and improve what we’re doing. Our website (https://oregonwinehistoryarchive.org/) is student-created and much of the content has been added by students. All the physical processing is done by students, as is a large part of the oral history interview process. So I love that part of my job – training, coaching, mentoring, and then watching what they can do. I think a lot of schools are hesitant to give students that much responsibility and freedom. And there are times when it’s a challenge. But with the right training, oversight and motivation, I think people would be surprised what students – even undergraduates who can’t legally drink wine yet – can do. They take a real ownership of our space, our collections and our image. They conduct themselves professionally and take great pride in their work. And the experiences they’re having, the skills they’re learning, the people they’re meeting… it’s truly priceless experience. And a big part of that is another favorite part of my job – the people in the industry itself. The Oregon wine industry has a reputation as a friendly, collaborative, welcoming industry, and in our case it has certainly been true. I have to imagine trying to do what we’re doing for certain industries would be like pulling teeth. But we’ve been welcomed with open arms. People in the industry are busy – incredibly busy – and yet willing to make time for us, whether it’s to answer questions or sit for an interview. They love working with our students and talking about the past, present and future of the industry to students who may be a part of that future. I can’t overstate how wonderful the industry is to work with. And they recognize the importance of what we’re trying to do, and they’re thankful for it. It’s incredibly rewarding. Meeting people in the industry, hearing their stories, tasting their wine… it’s an amazing way to learn about Oregon wine.

From left: Don Hagge, Rachael Woody, Rich Schmidt and Shelby Cook. Don Hagge, a former NASA engineer who now owns and operates Vidon Vineyard in Newberg, Oregon, answers questions during an oral history interview with Rich Schmidt on August 3, 2016.

Stay tuned for future posts in the “There’s an Archivist for That!” series, featuring stories on archivists working in places you might not expect. If you know of an archivist who fits this description or are yourself an archivist who fits this description, the editors would love to hear from you—share in the comments below or contact archivesaware@archivists.org to be interviewed for ArchivesAWARE!