Welcome to the first entry in the new ArchivesAWARE series, “Archival Authors.” Here we will feature archivists who have used their professional experience to inform books they have written for the general public. What inspired them? How does one write a proposal for a publisher? How did archivistics affect the tone or direction of their book? What did they want readers to take away?

In this first series post, Deirdre A. Scaggs, Associate Dean, Special Collections Research Center, and Director of the Wendell H. Ford Public Policy Research Center, shares how processing the papers of a poet and folksinger led her to explore values of family, shared experiences, and collective history.

While working at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) in 2012, I became intrigued with a set of recipes that were revealed during a processing project. Logan English was a poet and a folksinger who died fairly young in a car crash and his parents had donated his papers to SCRC. I couldn’t stop thinking about his recipes – many were stained, they contained plans for dinner parties with wine pairings, and Logan even wrote instructions for guests to write poems about their meals. I could tell that Logan had made these recipes, he had enjoyed this food, and shared meals with his friends and family.

I was struck by his story and it reminded me of how important family and shared meals were to me. It seemed like such a broadly relatable experience, and that while Logan was gone, this very tangible piece of him had survived. More than that, I wanted to experience it too. I became intrigued with the idea of bringing his archives to life through smell and taste, and shared experience. Before I knew it, I was actively searching for more recipes in other collections. I collected a small amount to test and write up and then I approached the University Press of Kentucky regarding a contract.

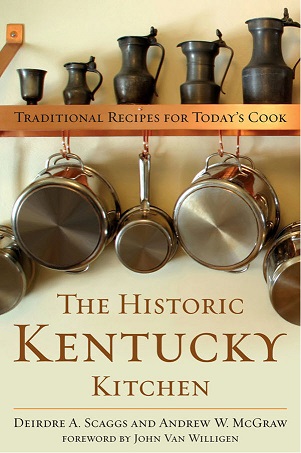

The Historic Kentucky Kitchen: Traditional Recipe’s for Today’s Cook (The University Press of Kentucky, 2013) is a book for the modern home cook. It is also a living history, steeped in Southern and Kentucky food culture. I want to acknowledge that attributing each recipe to a creator/maker was mostly impossible. This book was created from handwritten recipes saved by both wealthy and average families. Many of those early families would have had servants and cooks who were African Americans. I want to acknowledge their contribution even they could not be identified by name.

The Historic Kentucky Kitchen contains more than one hundred, mostly handwritten recipes, dating from 1850-1950. All of the recipes come from family papers or historic cookbooks in the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center (SCRC). Each recipe was tested, modernized, and curated for inclusion.

In conducting archival research for The Historic Kentucky Kitchen, I was looking specifically for handwritten recipes in the public policy archives, university archives, and manuscripts. Often these collection inventories were made before food culture and history became a popular topic of study. But being an archivist made a great deal of this research easier since I had broad knowledge of the collections, access to internal databases, and there was a team of students doing a reprocessing project on some of the earliest collections.

Handwritten recipes are often hard to read, they can be faded, or stained. Significant historic cooking research was required to interpret not only the process of cooking, but how to know what old measurements meant. We use standard measurements now, but historic recipes often include references to butter the size of an egg, a teacup of this, or a gill of that. In agreement with the publisher, I was seeking to create a well-rounded cookbook that focused on regional, Southern cuisine. So, I needed to find very specific recipes such as: mayonnaise, burgoo, bourbon, pound cake, biscuits.

Focusing on handwritten recipes was critical to me. I felt like these were the recipes that had familial significance, might have been passed down to family or friends, ones that were more likely to have been cooked, experienced, and been part of that family’s collective memory. For me, these unpublished manuscripts were the key to the success of my project. As mentioned above, I needed specific recipes to produce a complete project and so I opened my research to include early Kentucky cookbooks to fill in gaps that I was unable to fill with handwritten recipes.

My recipe research continued through the life of the project, although the bulk was focused during the first six months. I had seen cookbooks that were essentially reprints of historic recipes and for that reason they weren’t fully functional for a contemporary cook. I wanted to change perceptions that I had heard – that old recipes are bland to today’s palette. So, I had to test each of these recipes. I needed to select the ones that tasted the best. And, I needed to standardize the measurements, provide adequate instruction for cooking techniques and time.

It took two years to test recipes for the cookbook and there were plenty of failures, much trial and error, and wonderful success. It took another full year to write and edit the cookbook.

Upon publication there were a number of positive outcomes. I got to share my passion and research with colleagues, friends, school children, and people all across Kentucky and beyond. As a result of my talks, I generated interest in the preservation of food history and culture which prompted numerous collection donations to UK Libraries SCRC.

To me, these recipes represent our collective history. The traditions we share today were informed by that history and I believe this cookbook maintains that connection. The Historic Kentucky Kitchen is a truly functional cookbook with delicious meals that bridge the past and present. These recipes have been taken out of the archives to be made, shared, and to create new memories for future generations.