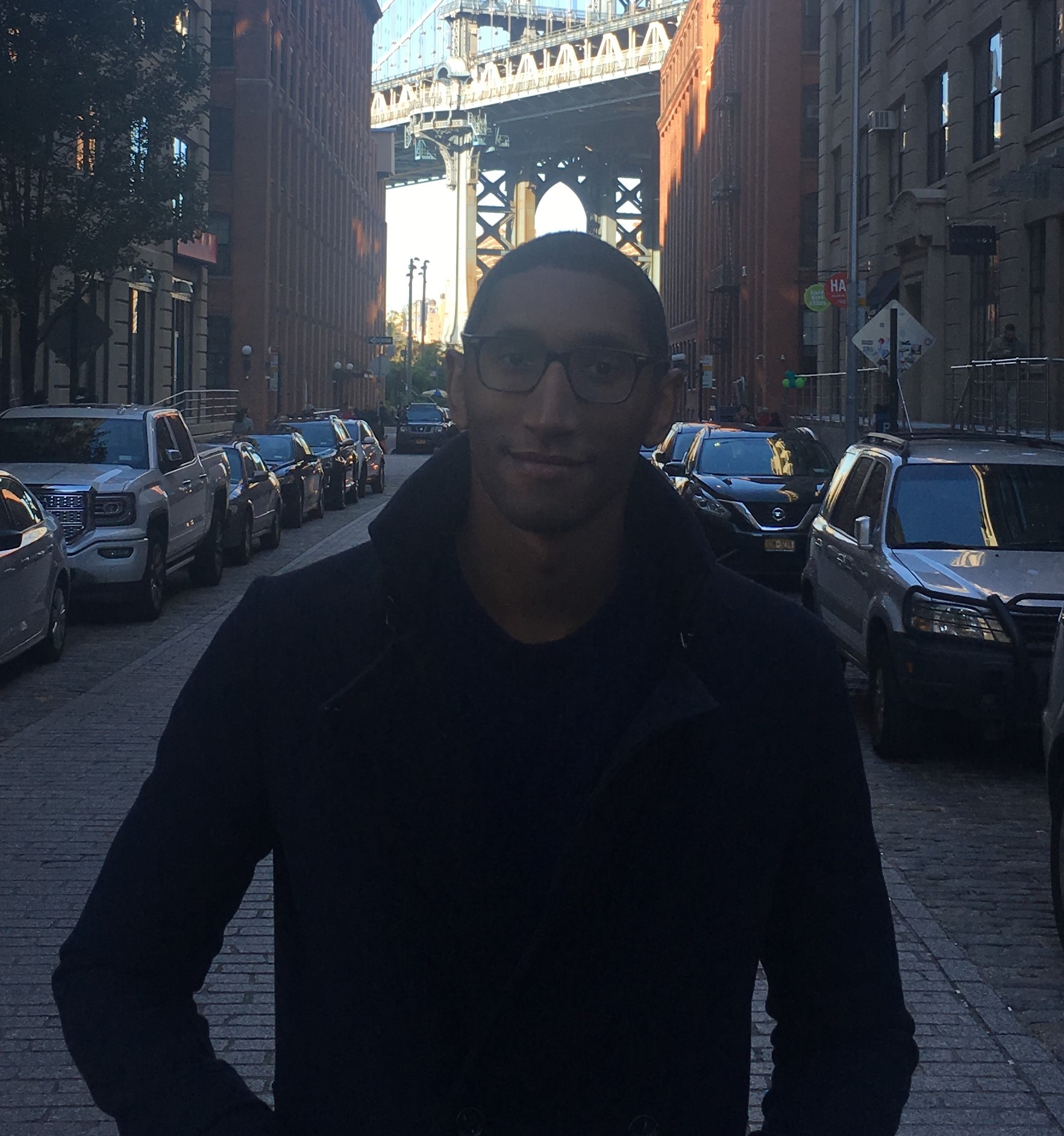

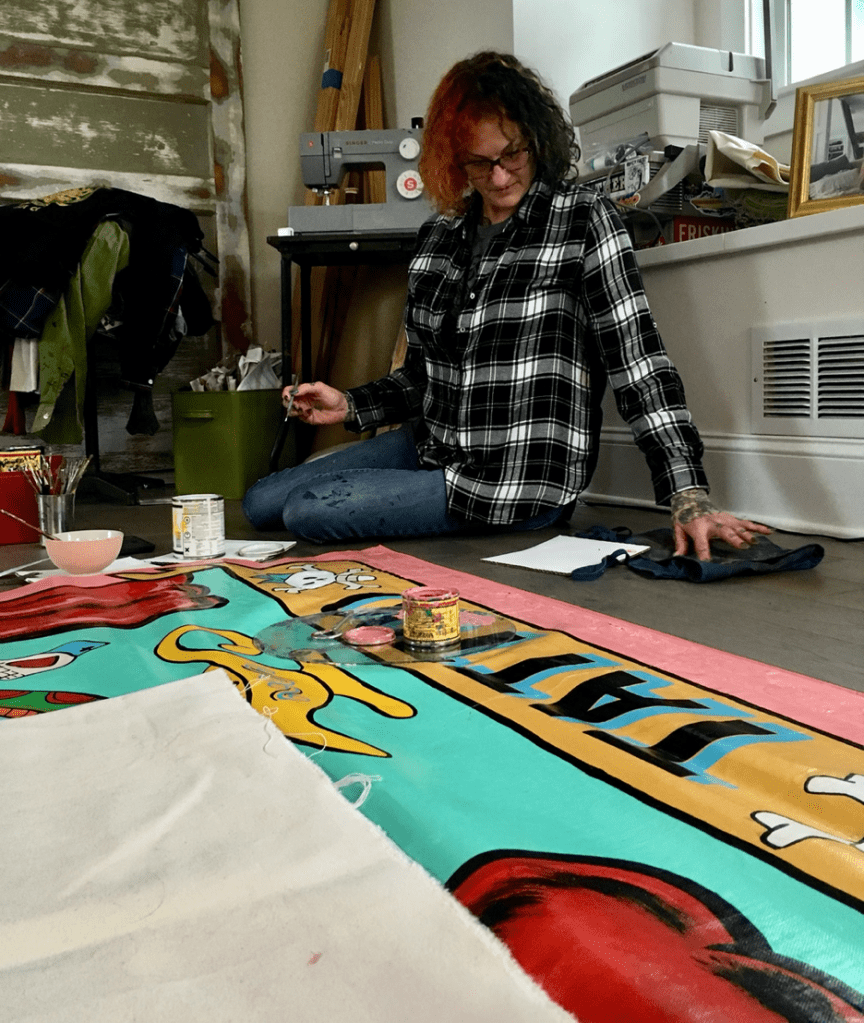

This is the newest post in our There’s an Archivist for That! series, which features examples of archivists working in places you might not expect. In this article, COPA member Angie Piccolo interviews Caitlin Oiye Coon about their job as Archivist at Densho.

How did you get your gig?

Caitlin Oiye Coon: In 2011, I was an early-career archivist in Seattle. I had written my graduate thesis on collective memory and the preservation of Japanese American incarceration photographs. In that project, I referenced Densho quite a bit. When I saw that Densho was hiring an archivist I knew I had to apply. The position combined my love of archives and my own personal connection to the incarceration. My dad’s family spent 1942-1946 incarcerated at Tule Lake. I grew up hearing stories from my grandma about her experiences there as a young woman. Luckily Densho hired me, and 12 years later I am the Archives Director and still excited to go to work every day.

Tell us about your organization

COC: Densho is a community-based archives and cultural heritage organization based in Seattle, Washington. We started out as a volunteer-led oral history project, recording stories of the World War II incarceration of Japanese American. We have spent the last 29 years interviewing survivors and their descendants, digitizing family collections, and creating educational content, all made available to the public online.

Describe your collections

COC: From Densho’s founding, our focus has been on providing access to all of our collections through digital platforms. All of our oral history and archival collections are freely available online in the Densho Digital Repository (DDR).

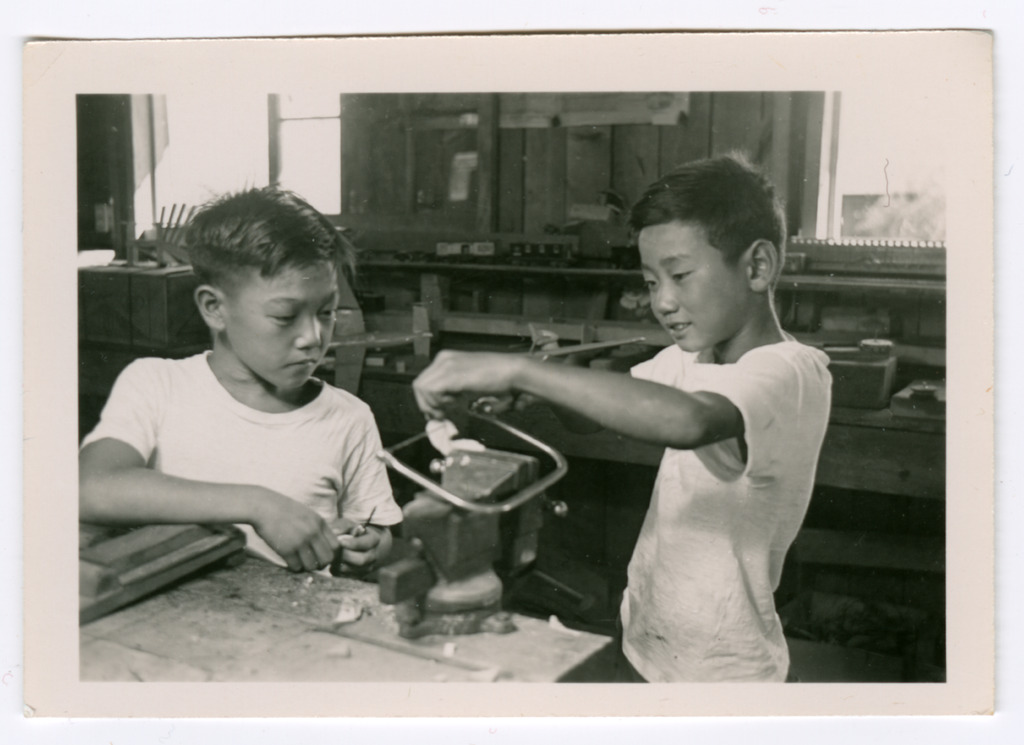

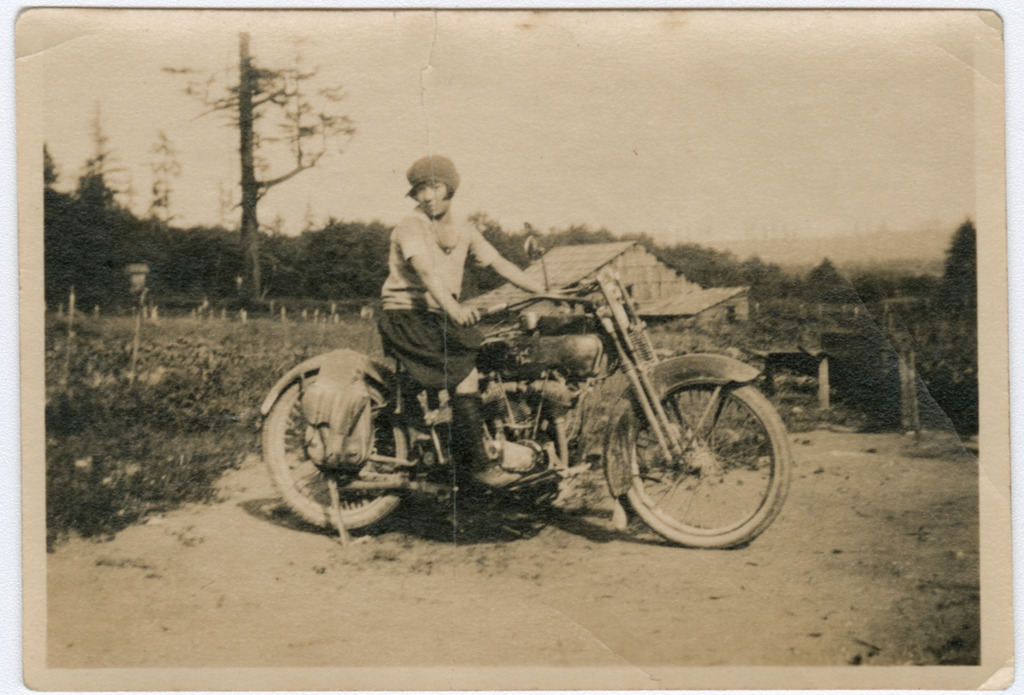

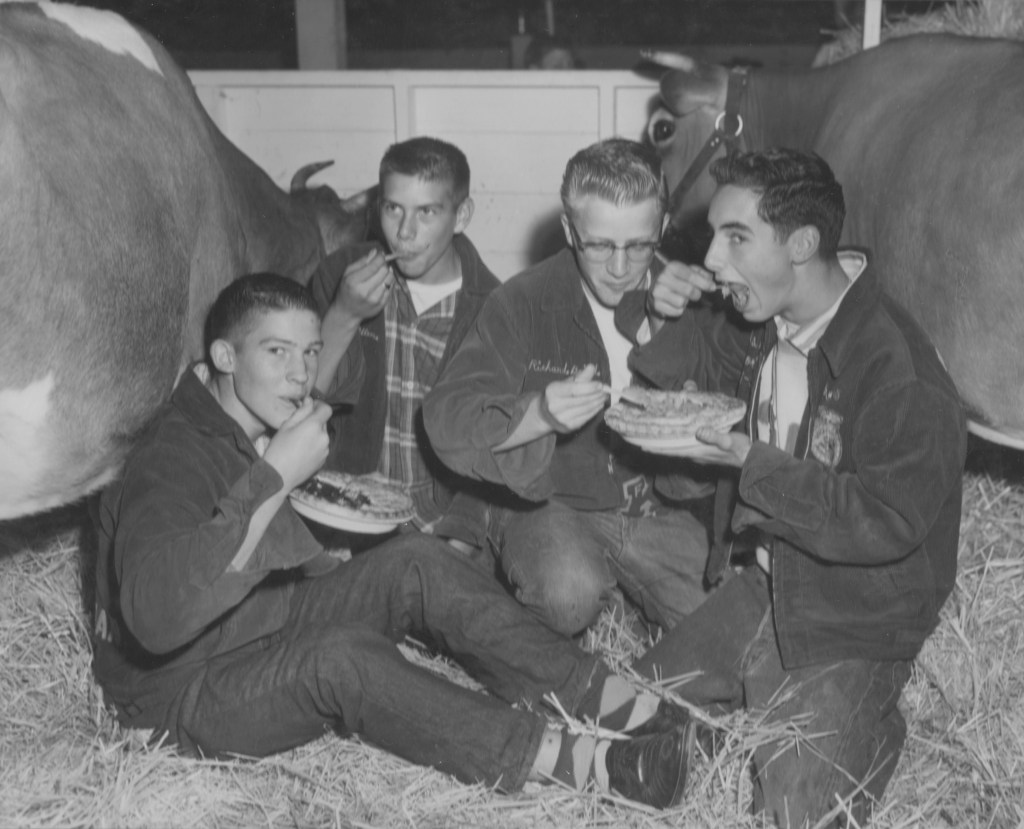

The DDR has over 1,000 oral histories and over 400 collections of digitized archival materials (photographs, letters, newspapers, documents, art, and ephemera) that range from one to thousands of objects. The focus of our mission is the Japanese American incarceration but we believe you cannot understand it in a silo, so our collections cover the broader experience from immigration to present day activism.

We are a post-custodial archives; we digitize materials and then return them to the original donors. This has been a great model for us because families can share their stories through the DDR but can hold onto the physical materials that mean so much to them. We also partner with many organizations who hold archival materials related to the Japanese American incarceration; providing technology, knowledge, or labor for smaller organizations and functioning as a secondary repository for larger organizations.

What are some challenges unique to your collections?

COC: Our biggest challenge comes from us being a completely digital platform and post-custodial archive. Over the years we have developed a good rhythm with the digitization process but it still takes a lot time. So, we are constantly working through a backlog of collections that cannot be viewed until they are published in the DDR.

What is your favorite part of your job?

COC: I love a lot about my job but I think the part that resonates the most with me is the connection to the community. We get to engage with so many families who were directly impacted by the incarceration. They all have different stories and they are fascinating to hear. Knowing that the community trusts us with those stories is gratifying.