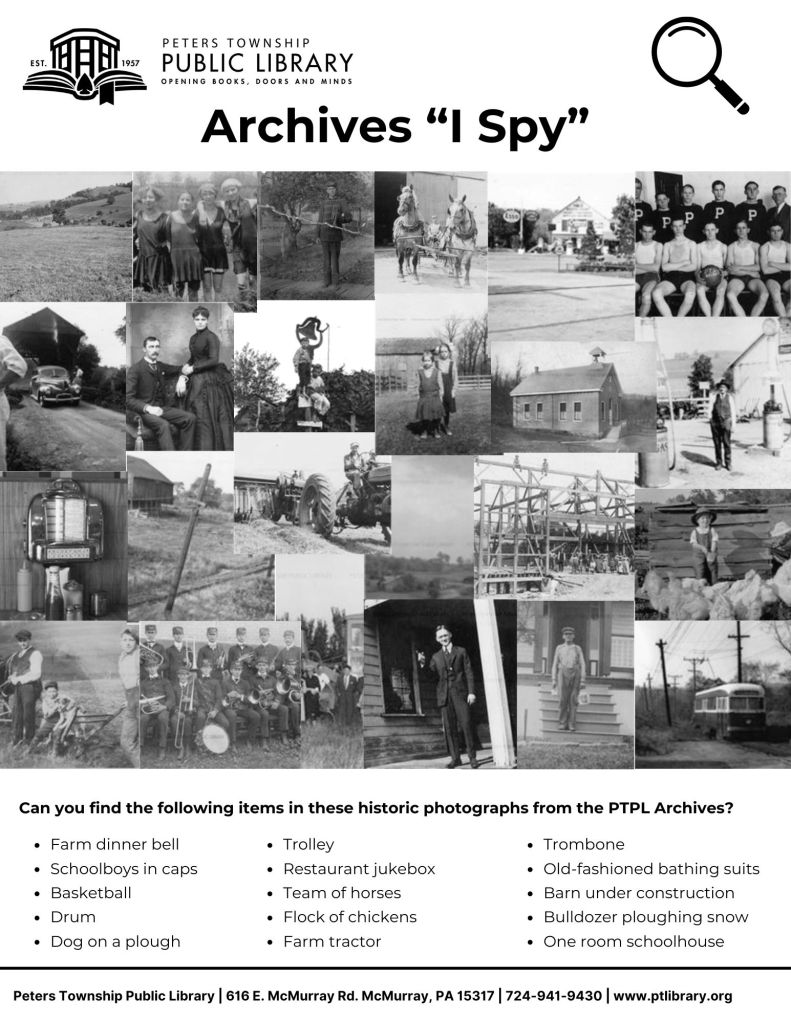

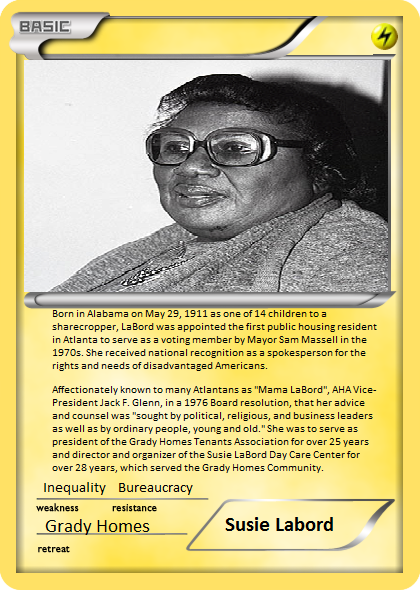

Photo provided by Rachel Thomas.

This series celebrates all the great information that exists in ArchivesAWARE!

This post originally published on May 12, 2020, challenges us to think about who we consider archivists.

This is the latest post in our series Responses and Retrospectives, which features archivists’ personal responses and perspectives concerning current or historical events/subjects with significant implications for the archives profession. Interested in contributing to Responses and Retrospectives? Please email the editor at archivesaware@archivists.org with your ideas!

Rachel Thomas, MA, is the University Archivist at George Fox University in Newberg, Oregon. She is passionate about the archival profession and opening the field to new professionals from all walks. Thomas is a member of Society of American Archivists and Northwest Archivists and recently served on the inaugural Northwest Archivists Archivist-in-Residence committee which is dedicated to working on the problem of unpaid internships in the archival profession. Linkedin profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rachel-thomas-5b21b38a

Six year ago I walked into my first professional gathering of archivists. As a lone arranger, I was excited to meet some of my colleagues. It was an unconference, inviting members of our profession to gather and discuss some of the issues surrounding our work. As the evening began, talk quickly turned to archives certification and qualifications. What makes an archivist and archivist? We gathered into groups to discuss this. I was excited to share my background and how I came to the field and hear how others entered this field I love.

However, as soon as we sat down, one of the members of my group said, “If you don’t have an MLIS, you are not an archivist. We have to have some standards!”

I was floored. I didn’t have an MLIS. I had just been hired by a university I respected, I had completed a MA in Early American and United States History, I had apprenticed in a large, well known, respected archive under a leader in the profession, I had worked for four years as an archive assistant at another university. I knew DACS, processing, other archival ethics and standards. I was a member of SAA and my regional association. I didn’t have my MLIS, but I was an archivist, wasn’t I?

As the discussion continued I found my voice. I expressed that I believed that being an archivist is about following the ethics and practices of the profession, not based on a certain set of letters behind a name. I shared examples of devoted archivists who had come to the field with no professional training. Some agreed with me, others held the position that the MLIS should always be required. The original speaker did not back down, she told me that she was sorry, but I didn’t belong in the field. According to her there were too many “non-professionals” calling themselves archivists and taking jobs from real archivists.

Eventually the night moved onto other topics. I learned a lot from colleagues in the room. I was able to network and build some contacts, learn about opportunities to serve in my regional professional organization. It was a successful evening by all accounts, however, I left doubting myself, hit hard with imposter syndrome.

A few years later and a few years wiser, I know that I am an archivist. I know I belong to the profession, and I know I bring value to my work. I have learned to appreciate my ability to think outside of the box, and largely credit it to the alternate route I took into the field. However, I still generally advise interns and students desiring to enter the field to pursue an MLIS. I know that it will prepare them well for the workplace, and I know that it has become a requirement for most positions in the field. I want them to be able to find work.

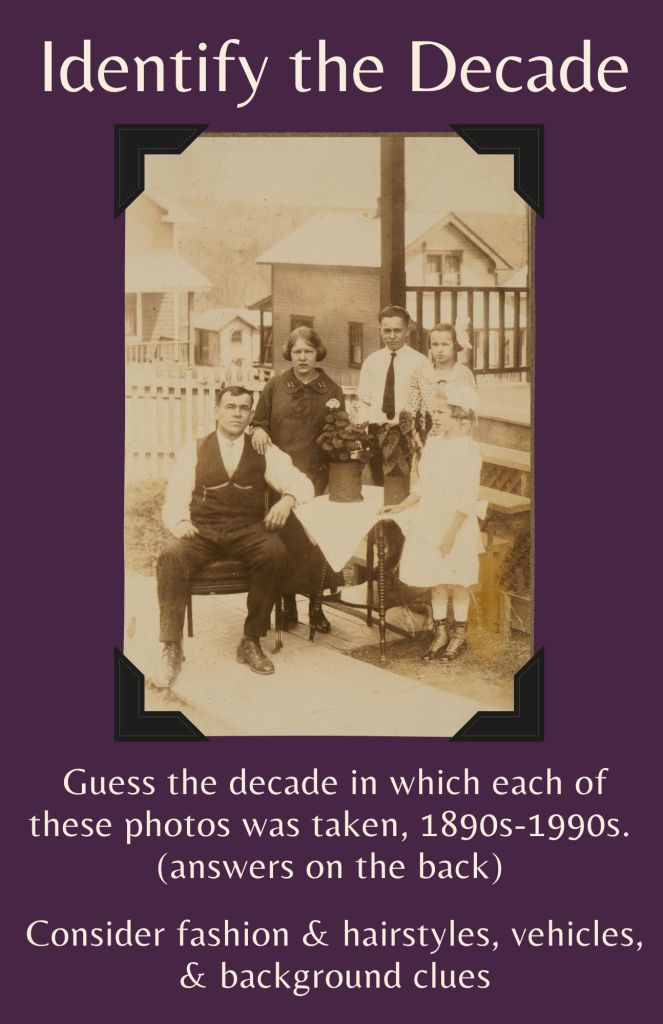

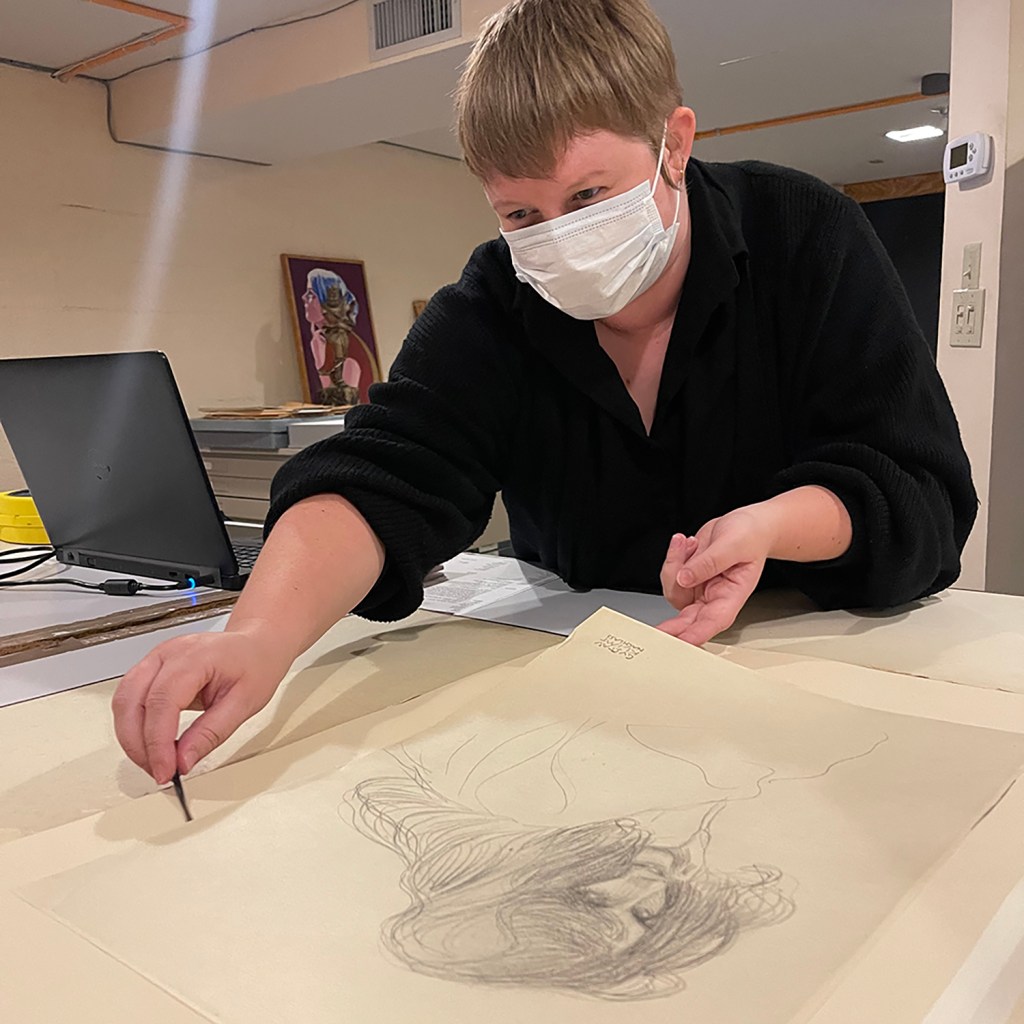

Photograph provided by Rachel Thomas.

At the same time, I want to challenge our profession to broaden their understanding of how one can become an archivist. I think we need to lean into the value of divergent perspectives brought by alternate education and career paths. We need to come to an understanding that the MLIS is not the only way to enter into our field. Other education and career paths can help us approach problems differently, they can help us develop new solutions, creative ideas, and the ability to diversify our collections and practices to fit a broader cross section of society. Employers must reconsider whether or not requiring the MLIS is unnecessarily limiting their applicant panel, disqualifying candidates who could bring new strengths and experience to the position. Archivists must check their assumptions about their colleagues. We must seek to be inclusive, not only in our collections, but among our colleagues.

This story does have a happy ending. At a recent conference I had a chance to have a heart to heart with one of the archival leaders in our region. He had been working as an archivist for decades and had received recognition at regional and national levels for his contributions. Everyone knew his name. I mentioned that sometimes I thought we were too focused on degrees in our field. That much of the work could be learned in other ways. That I had struggles with imposter syndrome because of my MA. He laughed, and said, “Guess I don’t belong in the field then! I only have a bachelor’s degree!”

This post was written by Rachel Thomas, MA. The opinions and assertions stated within this piece are the author’s alone, and do not represent the official stance of the Society of American Archivists. COPA publishes response posts with the sole aim of providing additional perspectives, context, and information on current events and subjects that directly impact archives and archivists.