This is the latest post in our new series Archival Innovators, which aims to raise awareness of the individuals, institutions, and collaborations that are helping to boldly chart the future of the the archives profession and set new precedents for the role of the archivist in society.

Dr Meral Ekincioglu (courtesy of Dr Meral Ekincioglu).

In this installation of Archival Innovators, SAA Committee on Public Awareness (COPA) member Rachel Seale interviews Dr. Meral Ekincioglu on her research project and its findings in regards to diversity and underrepresented architecture communities in archives at pioneering schools of architecture in the United States.

Please describe your innovative project.

As a scholar with Ph.D. degree in postwar architecture history and a member of Society of American Archivists (2019-2020), my current research project aims to investigate diversity and inclusion in current historical documentation practice at archives and collections established by pioneering schools of architecture in the country. As participants of my research project (archivists, curators and librarians in architecture) have indicated in their written responses, they don’t know such research study information so far. With the rising tension on women, politics of gender and other identity-based issues happening in schools of architecture in recent times, such as “Convergence” organized by Harvard University-Graduate School of Design-Women in Design Group where I was one of the panelists,1 my purpose with this research project is to stimulate a critical awareness of current strategies, policies and methods of historical documentation practice in architecture education with an emphasis on diversity and inclusion, and to establish a dialogue between the field of archive and architecture to make progress together on this subject.

With this research problem and concern, I contacted leading schools of architecture whose graduate programs were ranked the top ten (2018-2019) according to survey conducted by Design Intelligence 2 and published by Architectural Record. 3 In particular, my focal point has been “schools of architecture” because education is the core of all other dimensions of architecture, such as academic career, teaching, the construction of (critical) architecture history-historiography, professional (design) practice, etc. Architecture record archivist at the Yale University-School of Architecture; special collection archivist at the Harvard University-Graduate School of Design; librarian at the Princeton University- School of Architecture; 4 curator at the architecture and design collections at the MIT Museum; architecture, urban planning, and visual resources librarian at University of Michigan; art, architecture & engineering library; head of special collections at University of Rice; and library manager at the Kappe Library-SCI-Arch have kindly participated to my research project. In addition, the director at Archives & Records at the American Institute of Architects (AIA), in Washington D.C., has shared how the AIA has advocated for some research and archiving to document women in architecture and underrepresented groups of architects to increase diversity in the profession, and the AIA’s organizational records within this context.

Where did you get your idea and what inspired you?

The starting point of my scholarly and architectural concern about lack of diversity and inclusion in historical documentation of multicultural United States architecture has been my advanced academic research project on immigrant, foreign-born women architects and politics of gender that I conducted at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for two years. Secondly, following sentences (2016) by Professor Kenneth Frampton, architecture historian and critics at Columbia University have given a very significant impetus for my current research project: “….in trying to expand modern architectural critical history, the big issue is, what you include, and what you exclude…” 5 Thirdly, statements by Elizabeth Chu Richter (FAIA 2015 AIA President) has another motivation for me: “….There is plenty of anecdotal information that suggests there has been progress in building a more diverse and inclusive profession. Yet, the information is just that- anecdotal…..We need data, not anecdote…” 6 As the American Institute of Architecture-Diversity in the Profession of Architecture, Executive Summary (2016) also underlines, there is more work to be done to support and promote equity, diversity and inclusion in architecture, 7 and diverse and inclusive historical documentation in architecture is not an exception with this critical context.8 Finally, my architectural and personal roots come from Istanbul located in-between West and East cultures with its multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-religious history; and I worked as publishing coordinator and journalist in architecture. In other words, it is a natural desire for me to promote diversity in my expertise field due to my own roots, and effective communication among people, disciplines, fields and cultures has been always one of the important missions for me throughout my career in architecture.

What worked? What didn’t work? Were you surprised by the outcome or any part of your experience?

First of all, I would like to say that most of archivists, librarians and curators with whom I have contacted for this research project responded to me in a positive and supportive way. I think that they are deeply aware of critical issues related to diversity, equity and inclusion in today’s multicultural U.S. architecture. When I had the opportunity to meet some of them at their programs, they were very open to establishing communication, to know my own scholarly research experience on immigrant women architects & politics of gender, to discuss recent critical issues related to diversity, equity and inclusion in architecture. Their supportive approach and openness in communication have been very motivating for me to continue this research.

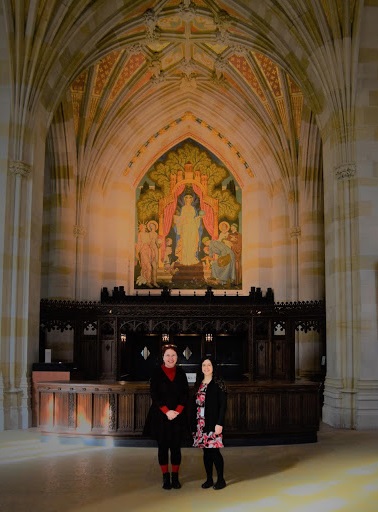

Dr. Meral Ekincioglu and Jessica Quagliaroli, Architecture Record Archivist at Yale University, School of Architecture (courtesy of Dr. Meral Ekincioglu).

In terms of surprising facts and outcomes of this research experience, the systematic documenting and collecting of historical documents at the schools of architecture who have participated to my research project did not seem to have a long history, according to participants’ written responses: The end of the 1960s – 1970s seem to be a threshold to establish their architectural archive programs or collections. More surprisingly, one of the architectural archives programs at a leading school of architecture began around 2000. If we remember, the historical background of the early architecture programs at major universities as first courses taught goes back in the country to the 1800s, and one of its characteristics is the role of immigrants from various cultures in its progress. With this historical background and characteristics, architecture education has been undergoing several challenging transformations in the early 21st century, like globalization. 9 Within this picture, the most well-known collections (including models, photographs, and architectural drawings, etc.) now in existence began to be developed since the 18th century in order to support teaching of architecture in the country as Alfred Willis points out in his essay. 10

In this respect, there seems to be a highly critical big gap in diverse and inclusive historical documentation practice at leading schools of architecture in the country, such as historical materials on pioneering profiles of foreign-born, underrepresented, minority students and professional -design- practitioners in their own history. Secondly, in spite of this critical picture, most of participants could not share a mission statement in effect to uncover, support and promote diversity in the content of archives and collections at their schools of architecture. Thirdly, although the architectural world has been using digital tools and apps extensively, and digital archives and collections enable everyone to search historical information and materials easier and faster, most of participants pointed out that their programs don’t have a digital archival project; one of them has a digitization project “underway”; one of them has “piloted” digital initiatives by scanning significant amounts of materials from their collections, etc.

Needless to say, increased access to historical materials for everyone has a remarkable potential to support and promote new findings and scholarly discussions on diversity, equity and inclusion in (multicultural US) architecture, its (critical) history and historiography. Among participants, the SCI-Arch library has a noteworthy project: Digitization SCI-Arch videotapes of public lectures which were approaching the end of their 40-year lifespan. Finally, we have been witnessing the appointments of women deans and head of departments in the US architecture in recent times, such as at MIT (J. Meejin Yoon as the head of the department of architecture, 2014-2018); Columbia (Amale Andraos as the dean of Columbia GSAPP, 2014-present); Yale (Deborah Berke as the dean of school of architecture, 2016-present); Princeton (Mónica Ponce de León as the dean of school of architecture, 2016-present); and Cornell (J. Meejin Yoon as the dean of Cornell University College of Architecture, Art and Planning, 2019-present). They have remarkable contributions to architecture in various ways. On the other hand, in terms of my research problem, one of the crucial questions is what those successful women’s academic leaders have brought to support and promote more diverse, inclusive and equal historical documentation practice at their programs and institutions in architecture so far; and what is their near future vision for this endeavor?

What’s next? Either for this project or a new development?

For this project, I plan to contact and to ask the same research questions to the next ten archival programs and collections at schools of architecture according to the same survey; and it would be great to bring together relevant archivists and architects to discuss together how to take steps for new developments on this subject. I completely agree with a participant’s comment: “there is a certain degree of inter-disciplinarity that needs to understood.” Needless to say, development in more diverse and inclusive collective memory in architecture might have a very positive impact on from pedagogical agenda to hiring practices, more diverse and inclusive workforce and leadership profiles for economic productivity in the field, more inclusive built environment and architectural spaces for everyone in the society regardless of their gender, race, ethnicity, etc. For this, I think that we (research community and practitioners in historical documentation in architecture) should collaborate with each other in a more effective way.

Dr. Ekincioglu with Professor Reif, the MIT President, after their conversation about her advanced academic research project on immigrant women architects, diversity and inclusion in –the US- architecture and historical documentation in the field (courtesy of Dr. Meral Ekincioglu).

What barriers or challenges did you face?

If I could reach out to some archivists and organizations relevant to my research topic, it would be great to comprehend this issue and to discuss what we can do together. 11 Open communication channels among various people and organizations, effective and long-term dialogue are very important to better understand the current problems, challenges and struggles for diverse, equal and inclusive architecture, and what can be done for historical documentation practice in light of these issues. In addition, according to the e-mail by Cornell University (on February 5, 2019), they did not have an archivist or a curator specifically attached to architectural and visual documents; so it was another challenge to find out their methods, strategy, policy etc. on diverse historical documentation for their own history. Finally, I could not find information if there is any recent data, survey etc. on the diversity in archivists and curators’ profile in architecture collections in the US.

How did you use archives /this project as a catalyst for getting different groups to talk to each other (cross-generational, cross-cultural, etc.)?

As a catalyst in-between archives and (critical) architecture history, in the coming months, I am very glad that my conference abstract has been accepted by “Midwest Archivists Conference (MAC) 2020 Annual Meeting” and hope to establish a productive bridge between two fields. In addition, two organizations have kindly invited me to present my project and discuss its findings with my concerns on diversity and inclusion. (Under current health issues, we have decided to re-schedule those presentations ). In addition, I have also contacted Boston Society of Architects, New England Society of Architecture Historians and the Archivist Round Table of Metropolitan New York Inc. to share my research studies on this topic. With those connections, I would like to bring into focus some questions and issues in-between two fields and professions; such as how can we raise awareness of each other’s work and research studies by considering recent critical discussions on diversity, equity and inclusion in (the US) architecture; what can we can do together (archivists and architects) to stimulate new architectural research on diversity, equity and inclusion, and for diversification of the archival records in architecture; what are long-held traditional practices, methods and policies in historical documentation of (multicultural US) architecture and how we can break down these traditions for more inclusive, diverse practice in this field; what are the changing role and responsibilities of archival programs and their practitioners as a response to rising influence of globalization, migration and gender-based political arguments in today’s (US) architecture; what are the expectations by archivists from scholars, professors, students and practitioners in architecture for more effective collaboration to support diverse and inclusive historical documentation.

What was your institution/archives like before you started developing this project? Does your institution have a history of supporting innovation in archives?

During my research studies at MIT, I have also created and developed a collection on pioneering Turkish women architects from the first (1930s-1960s) and second generations (1960s-present) for the Archnet that is partnership between the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) and the Aga Khan Documentation Center, MIT Libraries. (AKDC@MIT). This collection also includes a few significant (immigrant) Turkish and Turkish-American women architects with their contributions to postwar American and Turkish architecture. Archnet is is an open access on architecture, urbanism, environmental and landscape design, visual culture, and conservation issues as related to Muslim and Muslim-majority societies, their past and present. I think that there was a big gap in their sources on leading women profiles and documentation practice from those architecture cultures and geographic locations. As one of the significant feminist cases from modern, secular and Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East, women architects in modern and contemporary Turkish architecture have been a timely step to get attention to diversity in women architects (It is in-progress to upload the entire collection and its editing). In addition, following my appointment with the curator at the MIT Museum (Architecture and Design Collections) for my current research project (April 2019), I am so glad to learn that it was organized “Women of MIT Wikipedia Hackathon as a celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Department of Architecture” on August 6, 2019. 12 When I began my advanced academic research project on immigrant women architects in postwar US at MIT in 2014, one of my essential concerns was the lack of historical documentation on (diverse) women architects, and today, I am happy to witness such efforts at the Institute related to the history of its architecture program, one of the oldest one in its field.

Academic presentation by Dr. Meral Ekincioglu based on her archival research on pionnering Turkish and TurkishAmerican women architects in postwar US at the 71st Society of Architectural Historians, International Conference, St. Paul, MN, 2018 (courtesy of Dr. Meral Ekincioglu).

Thank you for this opportunity to reach out to your readers in archive and relevant fields to raise an awareness of diverse and inclusive architectural memory in today’s US.

Trained as an architect, Dr. Ekincioglu is a scholar in postwar architecture history and the subjects of her current academic study are politics of gender, multiculturalism, diversity and inclusion in her expertise field. Following her Ph.D. degree in Architecture, she conducted her advanced academic research project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-History, Theory and Criticism of Architecture Program for two years. Her scholarly endeavor brings into focus a critical insight into the politics of gender in institutional policies, academia, the profession, education, history and history-writing, and examines cross-cultural relations and transnational (design) practice in postwar architecture.

In her expertise field, she presented her research projects at the MIT-HTC Program, the International Women in Architecture Symposium at Virginia Tech., the MIT-Women’s and Gender Studies Program, the Women’s Studies Speaker Series at the CUNY-Graduate Center, Harvard University, the 71st Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) – Annual International Conference where she was awarded by a SAH fellowship. In addition, she was a panelist at “A Convergence at the Confluence of Power, Identity and Design” organized by the Women in Design Group at the Harvard University, Graduate School of Design, at “A Square and Half – The Colors, A Tribute by Ivaana Muse” at the MIT Museum, a speaker 51st NeMLA, Northeast Modern Language Association, Annual Convention at Boston University (Convention title: Shaping and Sharing Identities: Spaces, Places, Languages and Cultures), at WikiConference North America on reliability / credibility information at MIT, and “Media in Transition 5 and 6”, two international conferences organized by the MIT-Comparative Media Studies.

Her recent conference abstract, “Tracing Diversity in Historical Documentation of Architecture Education in the US” has been accepted by Midwest Archives Conference, 2020 Annual Meeting. Dr. Ekincioglu is also an author and a contributor of two international publication projects on women architects (forthcoming 2021).

Prior to MIT, she was a research fellow at the Harvard University, Aga Khan History of Art and Architecture, Ph.D. Program, and research scholar at the Columbia University, Graduate School of Planning and Preservation, Ph.D. Program for her Ph.D. dissertation research. She created and developed the collection, “Women in Modern and Contemporary Territories of Turkish Architecture” at MIT to contribute to documentation of diverse women architects profiles, conducted short documentary film projects on immigrant and underrepresented figures in architecture, and has a certificate by Consortium for Graduate Studies, Gender, Culture, Women & Sexuality (GCWS) at MIT. Dr. Ekincioglu was a member of Society of American Archivists (2019-2020).

Notes and references:

- See, https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/event/a-convergence-at-the-confluence-of-power-identity-and-design/, last accessed on 1.20.2020.

- See for its survey, https://www.di-rankings.com/most-admired-schools-architecture/, last access on 1.18.2020; for research methodology of this survey, see, https://www.di-rankings.com/methodology/, the last accessed on 1.9.2020.

- See for its publication, Gilmore, D., 2018, Top Architecture Schools of 2019, Architectural Record, September 4; https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/13611-top-architecture-schools-of-2019; the last accessed on 12.10.2019.

- Based on their e-mail on February 22, 2019, the Princeton University, School of Architecture was without an archivist at that time.

- See for Kenneth Frampton conversation at the Harvard University, GSD, ChinaGSD Distinguished Lecture: Professor Kenneth Frampton, “Chinese Architecture”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8asbjkin-W0&t=3756s, (1:01:06), 10.29.2019.

- See for its reference, Diversity in the Profession of Architecture Executive Summary 2016, the American Institute of Architects, http://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2016-05/Diversity-DiversityinArchitecture.pdf, p. 2, accessed on 10.15.2019.

- See, Equity, Diversity, And Inclusion Commission Executive Summary January 25, 2017, http://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2017-01/Diversity-EquityDiversityInclusionCommission-FINAL.pdf, accessed on 10.15.2019.

- At that point, I would like to underline a recent data project related to architecture history: The Society of Architectural Historians has just launched the SAH Data Project to collect information on the status of architectural history in higher education in the US. As it is indicated on their official link, their surveys aim to determine where and in what ways the field of architectural history is expanding, receding, holding steady, and to consider the structural or cultural factors behind such trends. See, “Society of Architectural Historians Launches Surveys for Study of Architectural History in Higher Education” by SAH News | Feb 21, 2020, https://www.sah.org/about-sah/news/sah-news/news-detail/2020/02/21/society-of-architectural-historians-launches-surveys-for-study-of-architectural-history-in-higher-education, last accessed on 3.15.2020.

- For a well-detailed and in-depth discussion on the history of architecture education in the US, see Ockman, J. (ed.), Williams, R. (research editor), 2012, Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America, published on the Centennial Anniversary of the Association of Collegiate School of Architecture, 1912-2012, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- See, Willis, A., 1996, “The Place of Archives in the Universe of Architectural Documentation”, The American Archivist, Vol. 59, No. 2, Spring, pp. 192-196; its link: https://americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.59.2.l54510w443504578, last accessed on 1.20.2020.

- Such as the current curator of Drawings and Archives at Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, the New England Archivists (NEA) and AIA New York’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee.

- See https://calendar.mit.edu/event/women_of_mit_wikipedia_hackathon?fbclid=IwAR0PEgbGMtQyNaQAUCpGmYhDRAgVYrzoBl9Ro cwJeSc0_AkiJYKzswYsZUw#.XgvjvUdKiM, https://mitmuseum.mit.edu/calendar/women-mit-wikipedia-hackathon; https://outreachdashboard.wmflabs.org/courses/MIT_Libraries_and_MIT_Museum/Women_at_MIT, (In celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Department of Architecture), last accessed on 1.15.2020.

Do you know an Archival Innovator who should be featured on ArchivesAWARE? Send us your suggestions at archivesaware@archivists.org!

![Krü Maekdo wearing t-shirt that says "Black Lesbian Archives Grassroots Tour 20[??]"](https://archivesaware.archivists.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2f9473ca-c4c0-418c-ba2e-ba41aa14641f.jpeg?w=253&h=624)

![Screenshot of Tweet by @alexiadpuravida Aug 4: Advocate that project positions ARE professional positions, not a pre-professional position [emojis show 4 hand claps] #saa 19 #s410 (symbols show 2 retweets, 24 likes)](https://archivesaware.archivists.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/screen-shot-2019-08-29-at-9.46.43-pm.png?w=620)